We all have stories to

tell—events in our lives that have led to insights we’d like to share—and some

of us would love to tell those stories through the medium of poetry. The

question is: How do we get from story to poem?

Narrative poetry (poetry that

tells a story) is based in the traditions of storytelling and folk tales. It

always has characters and a plot—there is action. A narrative poem usually

tells a story using a poetic theme. Our current understanding of narrative

poetry has traveled past epics and ballads and has evolved into more

contemporary forms. Foremost today, the poet should be aware of exactly what he

or she wishes to convey—to understand the purpose

of telling the story and what he or she wants to share with readers beyond the

story itself. In other words, the story itself becomes a taxicab for something

other. A narrative poem should lead to something more than the obvious

story—there should always be an implied or suggested meaning that goes beyond

the personal story in a narrative poem. You’re not just going to tell a story

about how your Auntie Martha lost the pearl necklace you hoped to inherit—your

narrative poem should lead readers to the larger meanings and associations of

loss and expectation. There’s a big difference between simply telling a story

and writing a poem.

Narrative poems sometimes fail to move beyond the anecdotal

and simply recount an experience that the poet has had. A great personal

narrative, though, has to be larger and more meaningful than an anecdotal poem.

In other words, a great personal narrative can’t rest on its anecdotal laurels

and must do more than simply tell a story. It needs to approach the universal

through the personal, it needs to mean more than the story it tells, and the

old rule “show, don’t tell” definitely applies.

Part I Guidelines

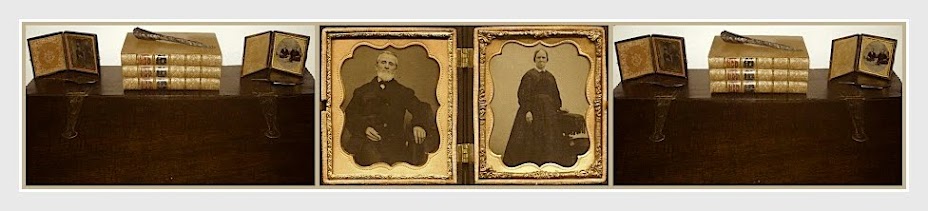

1. Think about a story that you really want to tell: something that

happened to you or to someone you know, a memory that haunts you, a family

legend, or a dream.

2.

Make a list (or do a free write) in which you record the important details of the story you want to write. Include the main

“characters” and a bit about their relationships to one another.

3.

You might find it helpful to make a chronological list of what happened.

4.

Remember that the “story” you tell should have a beginning, a middle, and an

end.

5.

The narrator of the poem doesn’t have

to be you—you have the option of

writing in the first, second, or third person. Consider a variety of

perspectives before deciding.

6. Decide upon the approach you’d like to take in your

personal narrative: chronological, flashback, or reflective.

Chronological—structure

your poem around a time-ordered sequence.

Flashback—write

from a perspective of looking back.

Reflective—write

thoughtfully or “philosophically” about the story you tell.

Part II Guidelines

1.

Start with a “bang” by beginning with a startling detail (or part of your

story). A good narrative poem doesn’t have to begin at the beginning of the

story. Move the story forward (and look back) from whatever your “point of

entry” may be (you may even start with the end of the story).

2.

Avoid explanations—it isn’t necessary to explain your story.

3.

Work on creating striking imagery, a strong emotional center, and

an integrated whole of language, form, and meaning.

4. Keep your poem on the shorter

side. That will mean leaving out all unnecessary details.

5. Be on the lookout for

prepositional phrases that aren’t essential (articles and conjunctions too).

6. Mark Twain wrote, “When you catch an adjective, kill it. … They

give strength when they are wide apart.” As you work on your narrative

poem, think about which adjectives your poem can live without. (Often the

concept is already in the noun, and you don’t need a lot of adjectives to

convey your meaning.)

7. Avoid clichés, abstractions,

and sentimentality—stick to your story.

8. Overstatement and the obvious

are tedious in narrative poems. Don’t ramble on—tell your story, but leave your

readers room to enter the poem, and leave a bit of mystery for your readers to

think about. (You don’t have to give all

the details of the story, just those that will enhance the meaning—your readers

don’t have to know everything you know about the story, just the most important

bits.)

9. End with an image, not an explanation. It isn’t necessary to tie your narrative up in a

neat package. Your dismount should be just as impactful as your first line.

10.

When you feel your narrative poem is close to completion, put it aside for a

day or two and then come back to it for editing. During

revision, it’s usually better to take out than to add. Find the lifeless parts

of your narrative and let them go. Be aware that telling a story and arranging

it in lines and stanzas aren’t enough to make it a poem.

Examples:

"The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere" by Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow

"Casey at the Bat" by Ernest L. Thayer

"The Walrus and the Carpenter" by Lewis Carroll

"The Raven" by Edgar Allen Poe

"The Legend of Gelhert" by Josie Whitehead

"The Pied Piper of Hamelin" by Robert Browning

"The Holy Grail" by Lord Alfred Tennyson

"Ave Maria" by Alfred Austin

"On Turning Ten" by Billy Collins