1. Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon by Caspar David Friedrich

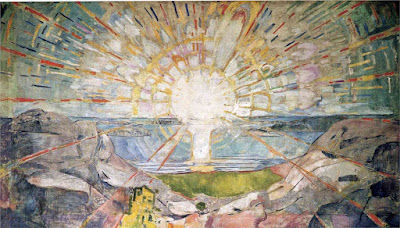

2. The Sun by Edvard Munch

3. Mountain Landscape with Bridge by Thomas Gainsborough

These days, with the pandemic still present and a threat throughout the world,

with so many related worries and concerns, and with all the other issues that affect our daily lives, it can be good to step outside of our "personal spaces" and enter the art world. I’ve selected three paintings (above) that I hope you’ll find inspirational. I worked with these paintings myself in my most recent book.

Our goal for this prompt is to write an ekphrastic poem based on one of the paintings above. If none of these painting works for you, feel free to choose any other.

Our goal for this prompt is to write an ekphrastic poem based on one of the paintings above. If none of these painting works for you, feel free to choose any other.

Importantly, Ekphrastic poetry is

more than mere textual description or verbal interpretation of visual art.

Making an object (painting or other work of art) lively before the reader’s eye

involves, in the best Ekphrastic poems, an emotional and perhaps even spiritual

response to the work of art— achieved through written language.

Guidelines:

1. Look at the paintings and choose one that especially appeals to

you.

2. Notice details within the painting you’ve chosen.

3. Then, jot down 10 or 12 things that in the painting that capture

your attention (and, hopefully, your imagination).

4. Think about how your items relate to one another, how they work

together to form a unified whole.

5. Jot down some notes about what you “see”—this will become your

“sensory pool.”

6. Free write for a while and begin thinking in terms of a poem.

7. Then, begin writing a poem that’s based on, about, or that

includes some of the items you noted. Look for connections among those

"things" and yourself. How and why do they "speak" to you?

What story might they tell?

8. Let your painting become the “emotion,” the “landscape,” or the

topic of your poem. Write in the present tense—here and now. Let your ten-twelve

items direct the content of your poem. Describe them, define them,

contextualize them, analyze them, repurpose them, recreate them. Let your poem take you where it wants to go.

Tips:

1. You can approach your

ekphrastic poem in several ways and, as the poet, it's your choice. You may

write about your experience viewing the art, about an experience the artwork

draws from your memory or a monologue or story you imagine coming from a voice

inside the painting. The choice is up to you, and what notes you

jotted in your sensory pool will help you pick.

2. Pay close attention to sight,

suggested sound, color, light, feeling, movement and other aspects of the painting you chose. Try

to disregard your analytical mind or any historical knowledge, and instead

experience the artwork through your senses. A poet doesn't need to "know"

facts about a piece of art. Instead, the poet experiences the artwork:

memories, sensations of smell or touch, impressions of the images you see

inside the art. These will help to inform your poem once you've decided on your

approach.

3. You may want to create a

dialog in which you journey in “conversation” between the painting and your

text.

4. Be sure to acknowledge the

artwork somewhere in your poem (I like to do this at the beginning of the poem,

just under the title).

5. Don’t just describe the artwork you’ve chosen; let the

artwork be your guide and see where it leads you. Relate the artwork to something else (a memory, a person, an

experience, a place, an emotion).

6. Work with strong images and,

if you tell a story in a narrative poem, be sure not to overtell.

7. Think about including some

caesuras (pauses) for emphasis, and leave some things unsaid—give your readers

space to fill in some blanks.

8. Pose an unanswered question or

go for an element of surprise. Let your poem take an interesting or unexpected

turn based on something triggered by the painting.

9. Look at the “movement” of the painting you’ve chosen and try to represent that movement in your line and

stanza breaks. For example, if a painting “moves” across the canvas, find a way

to suggest similar movement in the way you indent and create line breaks.

10. Most importantly, let the

painting you chose inspire you.

Examples:

All Examples are from Wind Over Stones, Welcome Rain Publishers, LLC,

Copyright © 2019 by Adele Kenny. All rights reserved.

This Almost

Night

(After Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon by Caspar David Friedrich)

It’s the way trees darken

before the sky … this almost night … another side of time and new. We think in

pauses and, in those pauses, everything (it seems) stands still.

The moon, rising, reorders

the sky, drifts and slips through clouds—sliver of moon, its nimbus pale, like

a word almost spoken.

A night bird lifts its shadow

away from the world, a world flown white with the ghosts of our passing

(thoughts vaguely remembered)—the sky dimmed to November gray, and us

moonstruck—what we thought we knew, fistfuls of winter we didn’t see coming,

this sack of rocks slung over memory’s shoulder.

This Particular Light

(After The Sun by Edvard Munch)

Weavers of the same place—beyond the

body’s dark containment, we entered the forest by our own choosing. Above us, galaxies

pitched and sieved through air—another degree of second thought. Having used up

all the words we knew for loneliness (and not sure what we found or what to

call it), we considered options (as if happiness might be a choice). Finally,

we returned to the larks’ twill, the blue jays’ liquid clicks—this life that is

not about what things are but what they mean (all gift, and so much more than

blood in the heart).

Do you remember the fox at twilight, the

edge of the woods like a mirror in rain? Face it, there’s only (ever) one whole

note—the minor third, the perfect fifth—gratefully, we turn from the dark’s

protective depth into the brimmed burning of this particular light.

Once, Late in

the Day:

East Canada Creek, Stratford, NY

(After Mountain Landscape with Bridge by Thomas Gainsborough)

I’ve come to see the sun

flick over stones in moments of gentle flashing, to think how fast a memory

becomes its own illusion. I’m here because what we call the soul—that almost

visual echo—is always close to holiness.

A birch on the shoreline

shapes itself to the breeze; aspens tremble as if this moment were all there is

between one beauty and another, between mystery and revelation. Here, there is

no revision, no opposite for recollection.

Once, late in the day, my

father and I fished beneath this bridge. I was seven or eight, and small trout

shone underwater, quietly golden. On the only road home, we were part of the

shadows’ perfection (trees and what was left of the sky). As we walked between

hills (close in the last light), my pail of water filled with stars, and the

sun came down, fallen from a larger light that, far too soon, my father walked

into and was gone.

No comments:

Post a Comment